Menu

Since 1985, Dr. Denise Herzing has been studying dolphin communication in the wild. She founded The Wild Dolphin Project, a non-profit scientific research organization that studies a specific pod of free-ranging Atlantic spotted dolphins (Stenella frontalis). The organization's long-term, non-invasive field research on wild dolphins gathers information on the natural history of these dolphins, including dolphin behaviors, social structure, communication, and habitat. With a three-year grant from Templeton World Charity Foundation (TWCF), Herzing and her team were able to develop a new software interface to explore one of the most intriguing aspects of dolphin communication: dolphin vocalization.

For this Q+A, we asked Dr. Herzing to share a little about her experiences and to describe how the tool her team has built is accelerating her research and that of others.

Briefly, how did you first become interested in dolphins, and how did The Wild Dolphin Project begin?

Denise Herzing: When I was 12 years old I use to page through the Encyclopedia Britannica (back when we had books) and stop at the whale and dolphin page. I kept thinking: wouldn’t it be interesting to understand their minds? They are social mammals, like the chimps and gorillas, but no one had studied them in the same way. So I set out to study marine biology and find a place in the world to observe them underwater. I founded the The Wild Dolphin Project to umbrella the work.

Pictured above: Dr. Denise Herzing records the sound and behavior of two Atlantic spotted dolphins near the ocean surface. Photo credit: Cassie Volker-Rusche.

Your Templeton World Charity Foundation grant focused on exploring linguistic richness in the vocalizations of dolphins. Please tell us why listening to dolphins matters.

Denise Herzing: Language is still the one big thing that separates humans from nonhumans. Do dolphins have it? If so, what is it like? We know that dolphins have great cognitive ability, including the ability to understand human-created languages, both acoustic and gestural. But yet, we haven’t had the opportunity to look deeply into their own communication system and see if they have language. TWCF's Diverse Intelligences program gave us the opportunity to focus on exploring this question, using existing vocal data from our long-term work in The Bahamas.

Nonhuman animals have now shown they can do many of the things we expect of intelligent species. They can use tools, they can project actions in time, understand abstract concepts. The one big area that still remains to be thoroughly explored is language. Imagine if other animals can have conversations with each other about the past or the future. We tend to think that animals just communicate about what is happening in real time, but one of the hallmarks of language is being able to plan, and to talk about things displaced in time, etc. So looking for language in dolphins is about exploring the process of finding diversity in intelligence, in this case around the use of language in an aquatic social mammal. Are there similarities or differences between social mammals on land vs. in the ocean? If so, what are they?

Your team is using machine learning algorithms to discover patterns in dolphin vocalization. Please describe a little about how that works.

Denise Herzing: Recently, there was an extensive article in the journal Science, talking about how machine learning is helping us understand animal communication. And there are some groups out there starting to collect sperm whale clicks to get some acoustic data. But the element that is much needed is the long-term observation and understanding of the society itself, something you can only get with long-term field work. The main process they laid out in their paper is exactly what we have been doing. It includes not only collecting underwater video and sound data, but also how the interpretation process will involve understanding the whole animal in its environment and social milieu. This will be the key to understanding the meaning of communication signals. We have been collecting our underwater video and sound data for 30 years, so we already have the ability to put it all in context for interpretation, which is pretty exciting! We can go back to our video dataset and find mothers and calves, or juvenile groups, and see if there are any consistencies for interpretation.

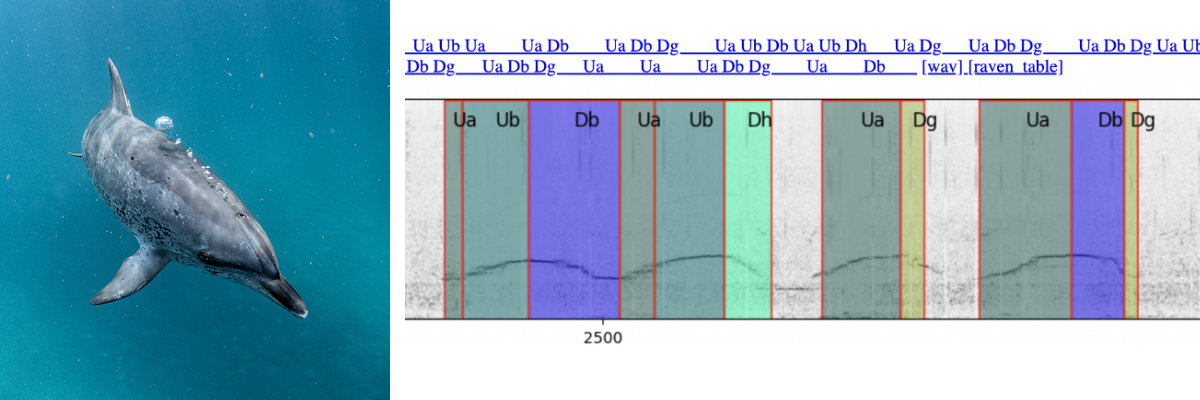

Pictured above, left to right: An Atlantic spotted dolphin vocalizing, as shown by the emitted bubble trail. Photo credit: Brittini Hill; A pattern detected in the communications signals Dr. Herzing and team have recorded.

What kinds of sounds do dolphins make, and what might they mean?

Denise Herzing: The Wild Dolphin Project has a vast database of underwater sounds and behaviors that have been collected over the past 3 decades from the free-ranging community of dolphins. Dolphins make three general types of sounds: whistles, clicks, and burst pulsed sounds. Whistles are primarily used for long distance communication and as contact calls between mothers and calves when they are separated. Clicks are primarily used for orientation and navigation. Clicks usually contain ultrasonic information above human hearing. Burst Pulses are packets of clicks spaced tightly together. These sounds are used during close proximity social behavior such as fighting. You can hear examples of these three kinds of sounds at The Wild Dolphin Project website.

What has your process of developing the pattern recognition software for exploring this data been like over your funding period?

Denise Herzing: After 3 years, and multiple iterations of a model, we now have a user interface that allows us to not only mine our data rapidly, but search for or query specific sounds or sequences of sounds. The idea is to look for order and structure in some of their vocal sequences, a basic requirement for any language.

The first 2 years were spent building models and testing what worked the best. It’s such a rapidly evolving field that new algorithms were popping up constantly. We used data we already had that was collected during our ongoing dolphin research in The Bahamas. Data was collected, for over 30 years, using an underwater video and hydrophone, part of our normal behavioral collection process. We know the resident community of dolphins, the individuals, their relationships. This kind of “metadata” will eventually help us interpret the meaning of sequences we find. We settled on using 5 years to start, as proof of concept, but we can eventually ingest all 30 years of data to explore their sounds.

Pictured above: Dr. Denise Herzing and Chad Ramsey, a computer scientist from the Georgia Institute of Technology in Atlanta at the research desk.

What do you hope that this tool will help researchers accomplish?

Denise Herzing: Our user interface is pretty exciting because it allows other researchers to explore their own data. Right now it is designed to work with small dolphin datasets/vocalizations. At the end of our funding period we had a workshop with Dr. Adam Pack and the UH Hilo's Marine Mammal Lab — our colleagues in Hawaii, who have a spinner dolphin dataset. We were able to train them a bit so they could start looking at their own data and asking questions. For example, one of the practical applications for them was asking whether or not the same individual dolphin could be detected from one side of the island to another. Searching through their dataset, looking for individual signature whistles, will help them determine this one basic question. It’s a lot quicker than spending months in a boat trying to photograph individual dolphins. By recording sounds 24/7, researchers can now query their data and ask about individual sounds, helping them to map out critical conservation areas.

What are some of the most memorable moments that you've observed or participated in over your time working with these animals?

Denise Herzing: There are many memorable moments! Some of them occurred during a simple observation like, oh, those juvenile dolphins are playing and then realizing that oh, those juvenile dolphins are going through similar motions as adults when they fight, but they are learning how to modify their communication signals appropriately! Sometimes these pieces to the puzzle were some of the most exciting moments of field observation. Another moment was clearly seeing how personality was so important in their social life. Some dolphins are shy, some are bold, and all these different types of personalities make up the whole society, and confer different advantages to survival.

Pictured above: A mother and calf Atlantic spotted dolphins. Photo credit: Liah McPherson.

Have you observed climate change affecting the communities of dolphins you study in recent years?

Denise Herzing: In 2004 and 2005 we had two main hurricanes directly hit our study site. Not that hurricanes are unusual in these areas, but after even these normal hurricanes, we lost 30% of all our dolphins. But climate change hit hard in 2013. Over 50% of our dolphins were displaced to a new location 100 miles away from their resident sandbank. After some oceanographic detective work, we determined that chlorophyll had crashed, and as a proxy for plankton, this likely meant that there was a big food crash in the area. In 2023, the displaced dolphins remain in their new home, trying to adjust to the local dolphin community. Many species will be driven together and end of competing for resources as their habitats shrink, or simply become uninhabitable.

What's next for you and The Wild Dolphin Project?

Denise Herzing: 2024 will be our 40th consecutive summer in The Bahamas monitoring Atlantic spotted dolphins. There are some great new technologies out there (drones, passive acoustic devices) to consider applying to our research. Yet our long-term video/sound dataset is probably the most valuable product we have. With all the new machine learning, and our own progress in this area, all the years of hard work tracking individuals and recording their communication signals may reap rich rewards as we try to “crack the code” of their communication with the new tools of artificial intelligence.

Pictured above: Dr. Denise Herzing, founder and director of The Wild Dolphin Project, with a high-tech underwater computer, known as a CHAT box. CHAT (Cetacean Hearing and Telemetry) receives sounds via two hydrophones, and produces sounds through an underwater speaker.

Do you have any advice or recommendations for others who are interested in the field? How can people get involved?

Denise Herzing: For students interested in a career, get experience. Volunteer, improve your skills, network. These are more important than your grades. And find your passion and train for it. For people interested in the Wild Dolphin Project, we involve citizen scientists in our work in the summer, which also helps fund our work. Please see the "participation" section of our website for information.

Spanning over three decades, The Wild Dolphin Project is the longest running underwater non-invasive dolphin field research project in the world. Their motto is "In their world...on their terms." With a focus on observing and recording behavior and sound, they are determined to "crack the code" of dolphin communication. Click here to learn more about Dr. Herzing and The Wild Dolphin Project team.